Paper Info

- Paper Name: Finding Bugs Using Your Own Code: Detecting Functionally-similar yet Inconsistent Code

- Conference: USENIX Security ‘21

- Author List: Mansour Ahmadi, Reza Mirzazade Farkhani, Ryan Williams, and Long Lu, Northeastern University

- Link to Paper: here

- Food: No food

Summary

- What is the problem? Probabilistically finding bugs is hard and often relies on large datasets to train on.

- How did they solve it? Classifying the analyzed code in two steps, first broadly by functionality then more specifically to detect inconsistencies, allowing bugs to be found with no external training data.

- How well did it work? 36 reported bugs out of 218 true inconsistencies out of 1,821 potential inconsistencies in QEMU/OpenSSL/WolfSSl/OpenSSH/LibTIFF.

Problems

Extensive work has been done on applying machine learning for vulnerability discovery in large code bases. Existing works generally follow a similar idea: train a model on a large dataset of programs vulnerable to a specific type of vulnerability and then use the model to detect previously unknown bugs in the wild. While this approach demonstrated success by finding numerous vulnerabilities, it also has significant drawbacks: (1) it requires a large dataset of vulnerable programs, which is hard to obtain and cleanse and (2) the approach is vulnerability-specific, it requires a large amount of manual effort to enable detection for new vulnerability types.

Detecting bugs as deviations from normal code is not new as well. However, previous works require domain expertise about bugs or manually-defined detection heuristics to identify dangerous code inconsistency, which makes vulnerability detection through code inconsistency analysis hard to scale.

How to detect inconsistency bugs in large code bases in a vulnerability-type-agnostic fashion becomes a problem. Further, a new technique is needed to remove the dependencies on large training sets, which are usually hard to obtain. In this paper, the authors propose FICS to address the aforementioned research questions.

Solutions

Compiles a given codebase in C into LLVM bitcode: It then employs an intra-procedural data-flow analysis to extract from each function small code pieces that represent basic operations or computations within a function since most security bugs and fixes tend to be limited within a single function and to make the analysis scalable to large codebases.

Uses Data Dependency Graph (DDG) without control edges as code representations. a Construct is a subgraph of a DDG, which represents a somewhat self-contained subroutine that is part of a function (e.g., processing a parameter to an API call). Any variable V used in a function F can be selected as the root variable for extracting a Construct C. In this case, the root ofC is the node in F’s DDG where V is defined or used for the first time (i.e., when V enters F). In other words, C contains all code statements inside F that compute on, or propagate,V.

For each function in a program, FICS extracts the Construct for every parameter and local variable of the function and every global variable reachable to the function. Given a DDG, the extraction starts from a specified node (i.e., the root) and traverses the DDG until all subsequent nodes are covered or the Construct max-depth is reached. All traversed nodes and edges then form a Construct. A root variable and the max-depth uniquely define a Construct.

Performs Construct abstraction. we preserve only the variable types for each program statement and remove all variable names and versions. We also eliminate all constants and literals from program statements.

Embedded into a node vector with instruction ID and the number of times the instruction appears in the graph (bag-of-nodes). We observed that, if edges are excluded from the similarity comparison, the common types of variations among similar Constructs no longer drastically affect the calculation of similarity scores.

Calculate the cosine similarity between their corresponding bag-of-nodes embeddings.

The connected-component algorithm groups similar Constructs in a program based on pair-wise similarity scores with similarity threshold tuned by users.

For each cluster of similar Constructs, the similarity between each pair of Constructs is calculated based on the graph2vec embeddings

Deviation analysis: Most bugs are due to missing or extra code fragments, such as wrong/missing checks (CWE131, CWE190,CWE253, CWE476, CWE475), missing variable initializations (CWE457), missing important calls like free or memset (CWE200), or redundant calls (CWE415).When expressed in a DDG, these bugs appear as a node deviation from their functionally-similar and correctly-implemented counterparts. For other bugs, such as wrong order of operations (CWE666), each manifests in a DDG as an edge deviation.

Evaluation

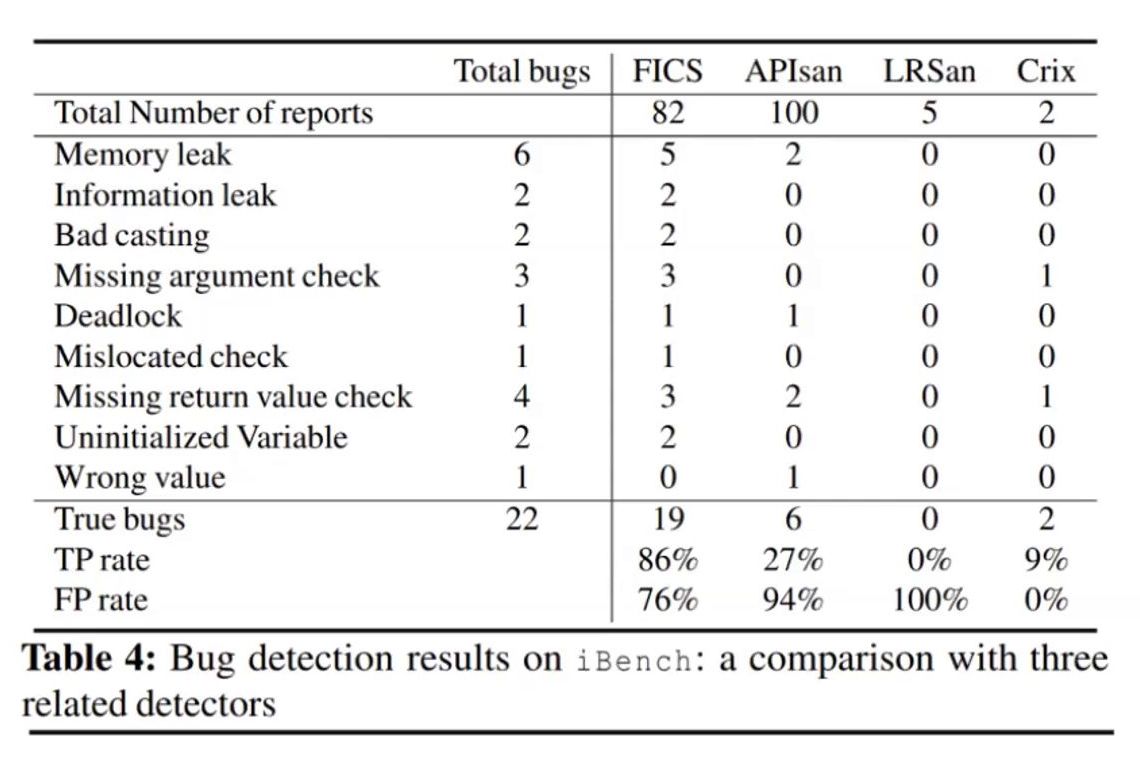

FICS was applied on five open source codebases. It managed to find 1821 inconsistencies out of which 95 were poor coding styles and 121 were potential bugs. 22 bugs have been confirmed by respective developer teams. Manual checking was required to decide on consistent and inconsistent constructs.

70 percent bugs were missing checks by developers(bounds checks, safety checks etc), 20 percent were call deviations and 10 percent were other factors such as casting, uninitialised variables etc. Evaluations were done on a workstation with 200 GB of RAM and 20 cores processor. Only OpenSSL and QEMU codebases needed more than 5 hours for evaluation.

There is no support for C++ code, only C code can be analyzed by FICS. Large codebases cannot be handled by FICS as RAM requirement keeps on increasing. FICS may not catch one liner bugs. To detect bugs, non-buggy code blocks with similar functionality are needed for comparison.

Discussion

This paper demonstrates that although clustering is generally considered a less accurate machine learning technique, it is able to successfully find bugs that more “sophisticated” machine learning algorithms are failing to do. Other machine learning techniques have been applied to static analysis before, but require significant data set acquisition and training. The concept of how to implement a clustering machine learning technique to uncover hidden patterns or data groupings without human intervention or training is definitely a novel approach.

The evaluation is not as thorough as it should have been. The paper had a very small test set - by only analyzing 5 software platforms, 3 of them being tied to cryptology brings up other concerns. Although the technique does successfully scale to large software products, is it robust enough to analyze different types of software? For example, clustering parameters need to be tweaked for different machine learning scenarios. Are the settings that the authors chose ideal for all situations or would other types of software programs require different parameters in order to be effective?

The evaluation should have focused on two goals: the ability to find bugs and the demonstration of a good true positive/false positive ratio. They were successful on the first goal, uncovering 22 bugs that were not found before, but did not adequately discuss the second. Another option would be to start with a ground truth of software with a known set of bugs. This would allow the authors to evaluate how many bugs were both successfully found and missed by FICS when compared to other approaches.

The paper also exhibits other self-imposed limitations, such as “having FICS focused on intra-procedural inconsistencies makes the analysis scalable to large codebases.” It is understandable that minimizing the focus of the algorithm was necessary to prevent an explosion in the number of results, but by ignoring intraprocedural consistencies, much of the complexity of large code base projects is ignored.

Another question is what about codebases with very large numbers of contributors? This is somewhat addressed by the inclusion of software such as openSSL, but this question could be explored a little bit more deeply. Does this technique favor consistent, homogeneous codebases with fewer contributors, rather than heterogeneous codebase projects where a large number of contributors are contributing on average much smaller amounts of code each?